Everything I Know About Dramatic Writing

In the words of playwright (and my favorite thinker on the subject of drama), David Mamet:

“Everything in life is drama. Drama relieves the burden of our consciousness. We attempt to unite groups of people and establish ourselves and our identity through the stories we tell.”

Storytelling is baked into the foundation of human communication. It is the way we make sense of the world, for ourselves and others, and the way we tell stories has emerged over literally millennia of oral tradition that’s shockingly consistent throughout the world.

Personally, I believe that the nature of how we tell stories as humans is a product of our shared experiences.

Consider that for most of us, personal growth takes effort and is almost always a direct result of overcoming adversity -- we change and become “new” people only by reconciling our original beliefs with the lessons we learn as a result of internal or external conflict, thus forming a new understanding of the world.

When we are children, the stakes are usually pretty low. We run around the house in our socks because it is fun. We slip and fall, and the pain of getting hurt teaches us that we should be more careful rounding the corners. As we grow older, the challenges and conflict become more substantial as the stakes get higher and higher. Navigating complex social situations, developing ethics, maintaining personal relationships, finding meaning in our lives and our work, understanding current events… All this growth revolves around conflict and resolution.

Thanks to psychological phenomenon like narrative transportation and the mechanisms baked into our brains like mirror neurons, stories allow us to communicate ideas and feelings with other people without requiring them to go through the same challenges. And because stories play such a powerful role in creating emotional responses in audiences, ideas conveyed through story are retained significantly longer and more accurately than ideas conveyed without a narrative.

To quote film director, Gareth Edwards from his Keynote at SXSW 2017:

"I believe that what's sort of going on is, as a race, we're kind of immortal - we reproduce and sort of have clones of ourselves - but the one thing you can't reproduce is experience. And so human bodies are like hardware, but stories are like the software that we sort of download into a child."

Screenwriter Brian McDonald has a similar take:

“Stories are the collective wisdom of everyone who has ever lived. Your job as a storyteller is not simply to entertain. Nor is it to be noticed for the way you turn a phrase. You have a very important job--one of the most important. Your job is to let people know that everyone shares their feelings--and that these feelings bind us. Your job is a healing art, and like all healers, you have a responsibility. Let people know they are not alone. You must make people understand that we are all the same.”

Storytelling is a tool that helps us retain and pass down knowledge and values, and as we’ve developed superior storytelling techniques, we’ve expanded our ability to share stories across time, space, and even cultures, but perhaps most importantly, they are our connection to each other.

They are also our best means to meaning. In the words of Robert McKee:

“Life is chaotic and meaningless, and you have to find your meaning. You must find the answer, you can't just live. That's the point of story: helping you find your meaning in life.”

We are hardwired for story. But… That doesn’t mean we’re all great at constructing good ones. I’ve spent a tremendous amount of my professional life writing, and it’s always one of the most rewarding and frustrating aspects of my work. Getting good at it has taken me a long time, it’s required a ton of practice, and a whole lot of books on screenwriting — and I’ve learned some things that I’d like to share.

So… How do we tell compelling stories?

The Elements of Story

In his short but highly influential book, “Invisible Ink: A Practical Guide to Building Stories that Resonate”, Brian McDonald writes:

“Stories are not complicated. They are, in fact, deceptively simple. But like anything simple, they are difficult to create.”

We’ve all heard and told countless stories, and the basic form could not be more straightforward:

Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.”

Every story contains a number of common elements, which we will discuss in increasing depth. They are:

Setting: Where the story takes place.

Character(s): Who the story is about.

Conflict: What the story is about.

Theme: What the characters (or the audience) learns through conflict.

...and in the best stories, all these elements working together will shape and define the:

Plot: The sequence of events that take place throughout the story.

Even the most basic fairy tales and nursery rhymes you’ve ever read will feature each of these elements. Take, for example, Humpty Dumpty.

Thanks for this nightmare, TurboTax!

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

[Introduces main character and setting]

[Conflict]

[New characters]

[Theme: Some things in life cannot be fixed]

And the all of the action that takes place inside the story - Humpty falling from the wall, and the effort made to put him back together - comprises a plot.

Nursery rhymes are inherently simplistic, but you can see the same elements (usually minus theme) in any decent logline. Here are a few examples:

“Set in unoccupied Africa during the early days of World War II: An American expatriate meets a former lover, with unforeseen complications.”

or…

“Two imprisoned men bond over a number of years, finding solace and eventual redemption through acts of common decency.”

or…

“In a world where costumed vigilantes are illegal, a group of former ‘superheroes’ investigates a conspiracy that appears to be aimed at killing them all.”

No matter how complex a story becomes, how it’s structured, or what it’s about, it will have these five elements. How they’re arranged and organized will vary, but over the past 4-5,000 years of human history - and especially since Aristotle’s “Poetics” (c.335 BC) - we’ve codified a number of ways to tell dramatic stories effectively.

In the end, stories are always about transformation: the journey a character takes to become a different person through struggle. This transformation is called a character’s “arc”.

Dramatic Structure

Before we can begin to talk about dialogue, character development, motifs and themes, we need to start with the essential framework of any story -- dramatic structure.

The most common structure for most stories, typically consists of three parts – a setup, confrontation, and a resolution.

The setup (Act I) is used to establish the setting, characters and tone, and then to introduce an “inciting incident” that kicks off the forward momentum of the plot. The confrontation(Act II) introduces challenges to the main characters and creates the dramatic tension that causes some change in those characters. Finally, in the resolution (Act III), the tension caused by the conflict ends – favorably or unfavorably to the main characters as the type of story requires (comedy, tragedy, etc.).

Setup, conflict, and resolution can also be understood in parallel to the Kantian philosophical concept of “thesis”, “antithesis”, and “synthesis”, as coined by the German Idealist philosopher, Johann Fichte.

In this conception, the thesis introduces an idea, anti-thesis presents a critical challenge to that idea, and then synthesis resolves the conflict between the idea and its challenge by reconciling the truth (or falsehood) of each, thus forming a new conclusion.

From my perspective, this structure is essentially universal because it’s how we all actually experience challenges and grow as individual human beings.

Storytelling techniques developed organically starting with the beginning of written language in Bronze Age, around 5,000 years ago, and began to see formal codification with Aristotle, Homer, Sophocles, Euripides, Aesop and other Greek writers.

There are many variations of this structure, but it's all broken down into three fundamental segments, and those could be described as a period of calm, rising tension, then resolution. Musical composition works the same way as pieces move from consonance, to dissonance (tension), and the eventual return to consonance.

But it wasn’t until comparative mythologist, Joseph Campbell (1904-1987) synthesized the insights of psychologists like Carl Jung & Sigmund Freud, with the work of ethnographers and folklorists like Arnold van Gennep that we gained a more substantial guide to archetypal storytelling.

The Monomyth

In his seminal 1946 book “The Power of Myth”, Campbell observed consistencies in the structure of myths from around the world. He distilled these observations into a storytelling form he describes as “The Monomyth”, which features a series of character archetypes, as well as a 17-stage structure.

Christopher Vogler expanded on Campbell's work in his book, “The Writer's Journey”, from which the following character archetype descriptions have been taken.

Hero: "The Hero is the protagonist or central character, whose primary purpose is to separate from the ordinary world and sacrifice himself for the service of the Journey at hand - to answer the challenge, complete the quest and restore the Ordinary World's balance. We experience the Journey through the eyes of the Hero."

Mentor: "The Mentor provides motivation, insights and training to help the Hero."

Threshold Guardian: "Threshold Guardians protect the Special World and its secrets from the Hero, and provide essential tests to prove a Hero's commitment and worth."

Herald: "Herald characters issue challenges and announce the coming of significant change. They can make their appearance anytime during a Journey, but often appear at the beginning of the Journey to announce a Call to Adventure. A character may wear the Herald's mask to make an announcement or judgment, report a news flash, or simply deliver a message."

Shapeshifter: "The Shapeshifter's mask misleads the Hero by hiding a character's intentions and loyalties."

Shadow: "The Shadow can represent our darkest desires, our untapped resources, or even rejected qualities. It can also symbolize our greatest fears and phobias. Shadows may not be all bad, and may reveal admirable, even redeeming qualities. The Hero's enemies and villains often wear the Shadow mask. This physical force is determined to destroy the Hero and his cause."

Trickster: "Tricksters relish the disruption of the status quo, turning the Ordinary World into chaos with their quick turns of phrase and physical antics. Although they may not change during the course of their Journeys, their world and its inhabitants are transformed by their antics. The Trickster uses laughter [and ridicule] to make characters see the absurdity of the situation, and perhaps force a change."

According to Campbell (and Vogler), these characters are found in myths from around the world, and they each serve a particular function in guiding and challenging the hero on his or her journey -- and that journey is the central focus of Campbell’s 1949 work, “The Hero With A Thousand Faces”.

Campbell summarized this journey as follows:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

But the specific form that this journey takes place is archetypal as well. The way Campbell describes it is as a circle, taking the hero first as far as possible away from his starting point, challenging him to completely abandon his previous understanding of the world in order to overcome the antagonist and become the fully-realized hero, before returning home.

For Campbell, this journey takes place over 17 steps in three phases, starting with the “Departure”:

The Call to Adventure: The hero starts off in a mundane situation of normality from which some information is received that acts as a call to head off into the unknown.

Refusal of the Call: Often when the call is given, the future hero first refuses to heed it. This may be from a sense of duty or obligation, fear, insecurity, a sense of inadequacy, or any of a range of reasons that work to hold the person in his or her current circumstances.

Supernatural Aid: Once the hero has committed to the quest, consciously or unconsciously, his guide and magical helper appears, or becomes known. More often than not, this supernatural mentor will present the hero with one or more talismans or artifacts that will aid them later in their quest.

Crossing of the First Threshold: This is the point where the person actually crosses into the field of adventure, leaving the known limits of his or her world and venturing into an unknown and dangerous realm where the rules and limits are not known.

Belly of the Whale: The belly of the whale represents the final separation from the hero's known world and self. By entering this stage, the person shows willingness to undergo a metamorphosis.

Once the hero has chosen to accept the call to adventure, we begin what Campbell calls the “Initiation”:

The Road of Trials: The road of trials is a series of tests, tasks, or ordeals that the person must undergo to begin the transformation. Often the person fails one or more of these tests, which often occur in threes.

Meeting with the Goddess: This is the point when the person experiences a love that has the power and significance of the all-powerful, all encompassing, unconditional love that a fortunate infant may experience with his or her mother. This is a very important step in the process and is often represented by the person finding the other person that he or she loves most completely.

Woman as Temptress: In this step, the hero faces those temptations, often of a physical or pleasurable nature, that may lead him or her to abandon or stray from his or her quest, which does not necessarily have to be represented by a woman. Woman is a metaphor for the physical or material temptations of life, since the hero-knight was often tempted by lust from his spiritual journey.

Atonement with the Father: In this step the person must confront and be initiated by whatever holds the ultimate power in his or her life. In many myths and stories this is the father, or a father figure who has life and death power. This is the center point of the journey. All the previous steps have been moving in to this place, all that follow will move out from it. Although this step is most frequently symbolized by an encounter with a male entity, it does not have to be a male; just someone or thing with incredible power.

Apotheosis: When someone dies a physical death, or dies to the self to live in spirit, he or she moves beyond the pairs of opposites to a state of divine knowledge, love, compassion and bliss. A more mundane way of looking at this step is that it is a period of rest, peace and fulfillment before the hero begins the return.

Ultimate Boon: The ultimate boon is the achievement of the goal of the quest. It is what the person went on the journey to get. All the previous steps serve to prepare and purify the person for this step, since in many myths the boon is something transcendent like the elixir of life itself, or a plant that supplies immortality, or the holy grail.

And finally, once the battle has been won, our hero must “Return” home now imbued with:

Refusal of the Return: Having found bliss and enlightenment in the other world, the hero may not want to return to the ordinary world to bestow the boon onto his fellow man.

The Magic Flight: Sometimes the hero must escape with the boon, if it is something that the gods have been jealously guarding. It can be just as adventurous and dangerous returning from the journey as it was to go on it.

Rescue from Without: Just as the hero may need guides and assistants to set out on the quest, oftentimes he or she must have powerful guides and rescuers to bring them back to everyday life, especially if the person has been wounded or weakened by the experience.

Crossing of the Return Threshold: The trick in returning is to retain the wisdom gained on the quest, to integrate that wisdom into a human life, and then maybe figure out how to share the wisdom with the rest of the world.

Master of Two Worlds: This step is usually represented by a transcendental hero like Jesus or Gautama Buddha. For a human hero, it may mean achieving a balance between the material and spiritual. The person has become comfortable and competent in both the inner and outer worlds.

Freedom to Live: Mastery leads to freedom from the fear of death, which in turn is the freedom to live. This is sometimes referred to as living in the moment, neither anticipating the future nor regretting the past.

Although Campbell’s terminology can be a bit obtuse, the Monomyth concept is worth understanding for many reasons. For one thing, once you understand it, you’ll begin to see aspects of it crop up in stories all over the world. In the words of one of the greatest dramatists, David Mamet:

“The Hero Myth doesn’t exist as a creation. It exists as an expression of our understanding of life.”

But especially if you’re a screenwriter or have aspirations towards dramatic writing, the Monomyth is critical to virtually every important book on the subject. Campbell created the foundation from which most modern plays and movies are written.

From Myth to Screen: Syd Field’s “Screenplay” Paradigm

There are few books on screenwriting more important than Syd Field’s 1979 classic, “Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting”. Fields is heavily influenced by Campbell and brings that influence into his understanding of not only story structure, but the development of the protagonist “hero’s” character:

“Joseph Campbell reflects in The Power of Myth that in mythic terms, the first part of any journey of initiation must deal with the death of the old self and the resurrection of the new. Campbell says that the hero, or heroic figure, 'moves not into outer space but into inward space, to the place from which all being comes, into the consciousness that is the source of all things, the kingdom of heaven within. The images are outward, but their reflection is inward.”

Field uses Campbell to explain why the structure of the story matters, but he also builds a screenplay structure around the Hero’s Journey.

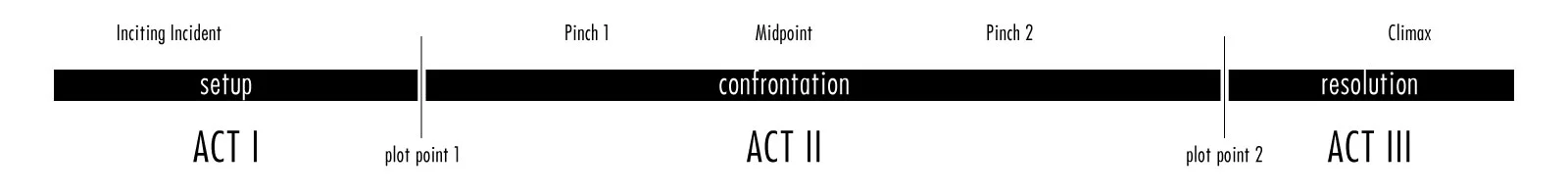

In what he called the “Paradigm”, Field expands on the standard Three Act form with additional elements, including the “Inciting Incident” (essentially what Campbell called the “Catalyst”), Plot Points 1 & 2, Pinches 1 & 2, the Midpoint and the Climax.

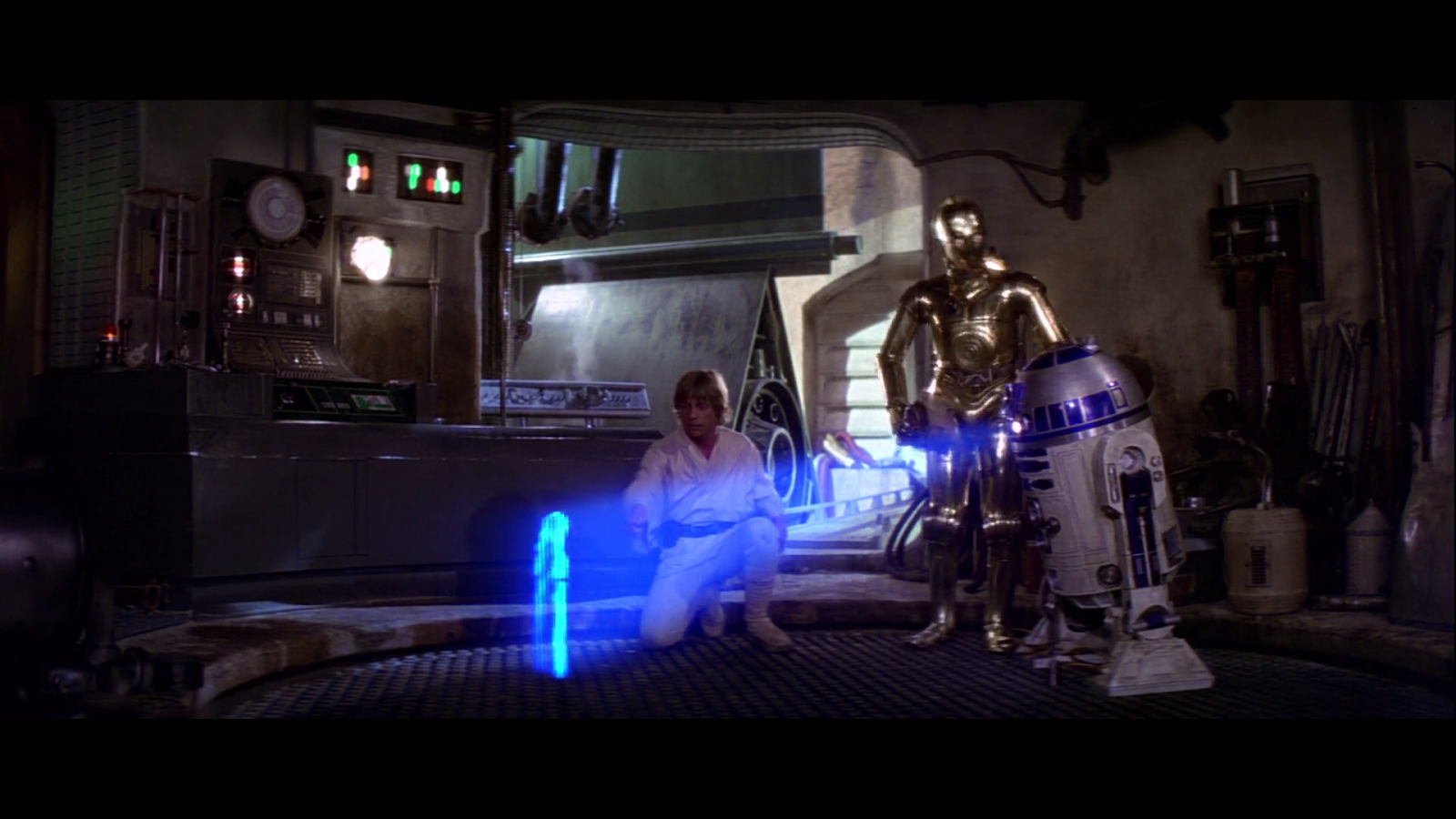

In Act I, we are introduced to the characters and the Inciting Incident that sets the plot in motion for the hero. In Star Wars, for example, this would be the moment that Luke sees R2D2’s recording of Princess Leia asking Obi-Wan Kenobi for help.

Inciting Incident

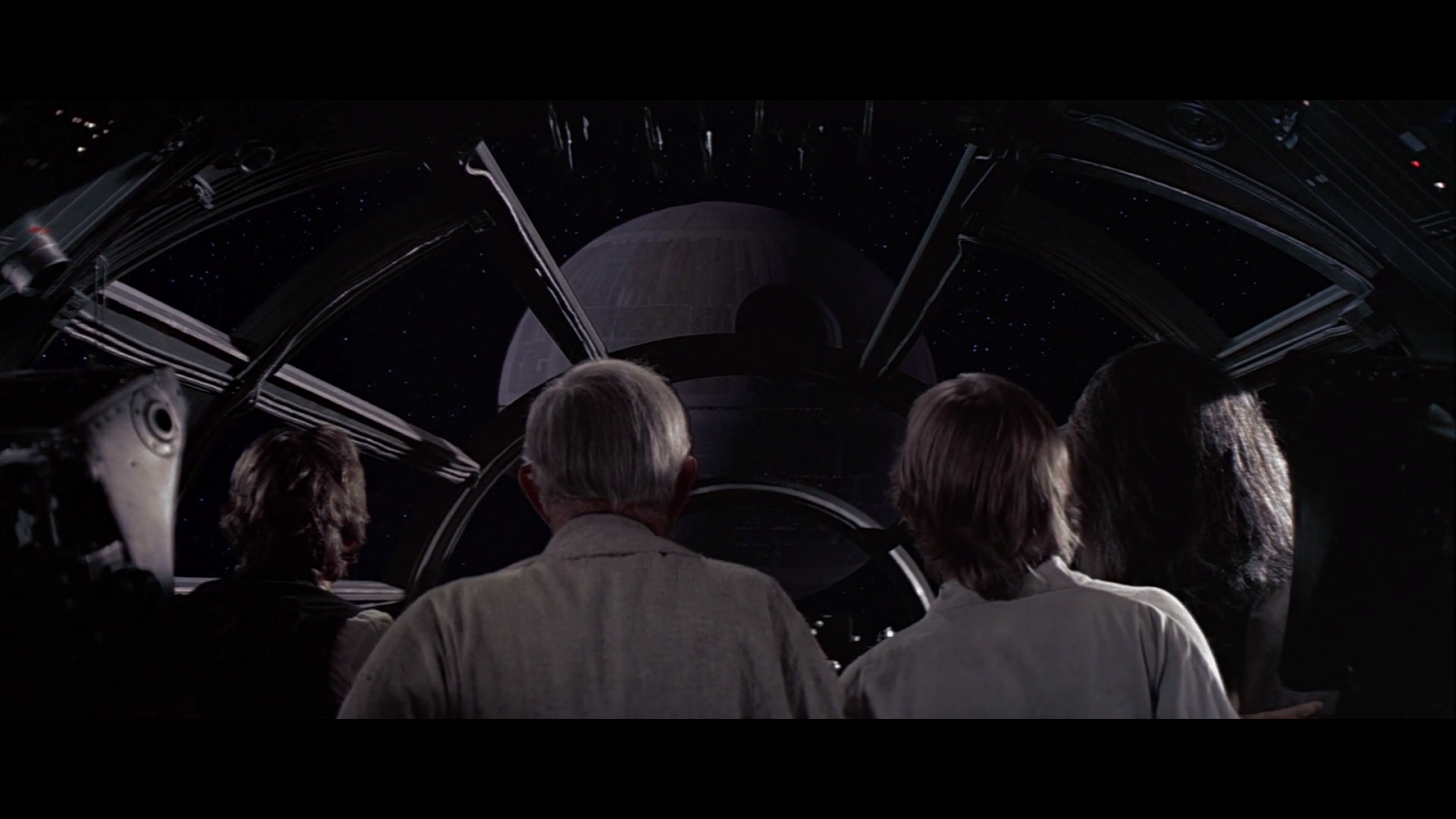

Plot Point I is the moment in the film where the hero chooses to enter the action of the main plot. For Star Wars, this would be the moment where Luke and Obi-Wan head to Mos Eisley, meet up with Han Solo & Chewbacca, and leave Tattooine for Alderaan. This is the first critical turning point in any story -- where Act I becomes Act II.

Then the fun begins!

In Act II, our hero faces obstacles, culminating first in Pinch 1 where they get into serious trouble, then the Midpoint where the film takes a more serious turn, and Pinch 2 where the stakes are significantly raised.

Continuing the Star Wars analogy, the first Pinch is when Grand Moff Tarkin and Darth Vader use the Death Star to blow up Leia’s home planet of Alderaan while she is forced to watch. The midpoint features a bevy of important plot elements all at once -- Tarkin realizes Leia won’t talk and sentences her to death, our heroes exit hyperspace to find Alderaan destroyed, and then the Millennium Falcon gets caught in the grip of a Death Star tractor beam, ensuring that they can’t escape. Finally, Pinch 2 finds our heroes caught in a garbage masher and they have to escape before the plot can move forward.

Midpoint

Once we get to Plot Point 2, our hero is in serious trouble -- otherwise to be understood as the point of no return. At this moment, there is frequently an important bit of information revealed to the protagonist, and his path is changed forever. Again, looking at Star Wars, that moment comes when Obi-Wan Kenobi (Luke’s mentor in The Force and last remaining link to his home and the way things were) is killed by the intergalactic villain, Darth Vader. Once Obi-Wan dies, there’s no turning back for Luke.

Finally, as the hero regroups and prepares for hs final confrontation, we enter Act III.

In Star Wars, this is where Luke, Leia, Han & Chewbacca rendezvous with the Rebellion Forces and plan to mount an attack on the Death Star. From there, it’s a clear (if dramatically rocky) path to the Climax, wherein Luke Skywalker blows up the Death Star using his newly discovered connection to The Force, saving the galaxy from the Evil Empire.

Climax

Field’s book is worth reading in its entirety for its invaluable advice on character writing, dialogue, plot, and advice on writing for film & television specifically. But perhaps its most powerful piece of advice is that before a writer even begins to attempt dialogue or plotting the story, he or she must know for certain how a story begins, how it ends, and exactly what happens at Plot Points 1 & 2.

I’ve learned over the years that this is not only “important”, it’s actually essential.

Without this information, you literally cannot write. By definition, plot is the forward motion of your story, and if you don’t know where it starts or ends, then you have no idea where the story is going. Understanding the four critical plot points will help you stay on course.

Once again, David Mamet says:

“A play has to have a precipitating event, before which, the play didn’t exist. And the precipitating event has to inspire the hero on a goal -- a journey -- that has a specific end, at the end of which the question that was raised at the beginning has been answered, either in the positive or the negative… We’ve stated a proposition and we’ve solved it. Anything which is not on that line has to be thrown out.”

All that said, where it comes to plot structure, there’s another screenwriting guru besides Syd Field that has made an even more substantial impact on my thinking.

Saving the Cat with Blake Snyder

In 2005, screenwriter Blake Snyder wrote a new book called “Save the Cat!: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need” and the title might not be overstating the case. Snyder’s book has become one of the most valuable books I have ever read on the craft of screenwriting.

It has plenty to offer in terms of character writing -- indeed, its title is a simple way of encouraging writers to make their heroes relatable and actually heroic by showing them doing something simple such as saving a cat from a tree. But in my opinion, the two biggest contributions Snyder made to the craft of screenwriting are:

Significantly expanding on Syd Field’s story form by incorporating even more from Campbell & Vogler; and…

Adding a set of 10 story archetypes — each of use the same screenplay form, but which feature different sets of situations and characters.

Let’s start by looking at Snyder’s structure, as an improvement on all of the ones we’ve seen before (with percentages that reflect where each beat fits in the context of a standard 120 page screenplay):

Opening Image (1%)

Theme Stated (5%)

Set-up (1-9%)

Catalyst (10%)

Debate (10-25%)

Break Into II (25%)

B-Story (30%)

Fun & Games (30%-50%)

Midpoint (50%)

Bad Guys Close In (50-66.6%)

All is Lost (66.6%)

Dark Night of the Soul (66.6-80%)

Break Into III (80%)

Finale (80-100%)

Final Image (100%)

To explain what each of Blake Snyder’s beats really mean, allow me to lean on blogger Tim Stout’s fabulous quick synopsis/breakdown:

Opening Image: A visual that represents the struggle & tone of the story. A snapshot of the main character’s problem, before the adventure begins.

Set-up:Expand on the “before” snapshot. Present the main character’s world as it is, and what is missing in their life.

Theme Stated (happens during the Set-up): What your story is about; the message, the truth. Usually, it is spoken to the main character or in their presence, but they don’t understand the truth…not until they have some personal experience and context to support it.

Catalyst: The moment where life as it is changes. It is the telegram, the act of catching your loved-one cheating, allowing a monster onboard the ship, meeting the true love of your life, etc. The “before” world is no more, change is underway.

Debate: But change is scary and for a moment, or a brief number of moments, the main character doubts the journey they must take. Can I face this challenge? Do I have what it takes? Should I go at all? It is the last chance for the hero to chicken out.

Break Into II: The main character makes a choice and the journey begins. We leave the “Thesis” world and enter the upside-down, opposite world of Act Two.

B Story: This is when there’s a discussion about the Theme – the nugget of truth. Usually, this discussion is between the main character and the love interest. So, the B Story is usually called the “love story”.

The Promise of the Premise: This is when Craig Thompson’s relationship with Raina blooms, when Indiana Jones tries to beat the Nazis to the Lost Ark, when the detective finds the most clues and dodges the most bullets. This is when the main character explores the new world and the audience is entertained by the premise they have been promised.

Midpoint: Dependent upon the story, this moment is when everything is “great” or everything is “awful”. The main character either gets everything they think they want (“great”) or doesn’t get what they think they want at all (“awful”). But not everything we think we want is what we actually need in the end.

Bad Guys Close In: Doubt, jealousy, fear, foes both physical and emotional regroup to defeat the main character’s goal, and the main character’s “great”/“awful” situation disintegrates.

All is Lost: The opposite moment from the Midpoint: “awful”/“great”. The moment that the main character realizes they’ve lost everything they gained, or everything they now have has no meaning. The initial goal now looks even more impossible than before. And here, something or someone dies. It can be physical or emotional, but the death of something old makes way for something new to be born.

Dark Night of the Soul: The main character hits bottom, and wallows in hopelessness. The Why hast thou forsaken me, Lord? moment. Mourning the loss of what has “died” – the dream, the goal, the mentor character, the love of your life, etc. But, you must fall completely before you can pick yourself back up and try again.

Break Into III: Thanks to a fresh idea, new inspiration, or last-minute Thematic advice from the B Story (usually the love interest), the main character chooses to try again.

Finale: This time around, the main character incorporates the Theme – the nugget of truth that now makes sense to them – into their fight for the goal because they have experience from the A Story and context from the B Story. Act Three is about Synthesis!

Final Image: opposite of Opening Image, proving, visually, that a change has occurred within the character.

The beauty of Snyder’s approach is that he’s synthesized almost everything that’s come before into a set of story beats that can be applied to almost any screenplay. He also proposed a series of 10 story genres that are commonly used in dramatic storytelling, which I think serve as both a valuable means of categorization and a useful place to start when considering writing a new story.

I often use this structure even when building documentary projects.

For example, the following are my original structural notes for Made in Mékhé, a documentary film I executive produced for the Foundation for Economic Education.

Made in Mékhé’s Opening Image

Act I:

Opening Image: Music + B-Roll of impoverished Senegal. Magatte Wade explains the idea of Tiossan. We see that Senegal is very poor.

Theme Stated: How do countries prosper? [The rest of the film needs to be about this and essentially nothing else].

TITLES

Set-up: Where are we? Who is Magatte? Why does she care about this little town? What's going on here?

Catalyst: What compels Magatte to start businesses -- how is this tied to the theme? How will starting businesses help Senegal, and in particular her town, escape poverty.

Debate: What are the challenges to starting businesses in Africa? Maybe in this part we just tease a few big issues, but share something about why Magatte ultimately decides to do it anyway. This is her story, so think of her as the protagonist.

Act II:

B-Story: Magatte's businesses have connected her with tons of wonderful people. Introduce us to these people. Show how great they are and that will help everyone understand how vital it is that Magatte's project of bringing more entrepreneurship to them succeeds. This might also be the perfect spot for Magatte's bit at 28m, where she explains how obvious it is to her that business is necessary to prosperity. However… We should also see that there are…

Bad Guys Close In (Problems Everywhere!): It seems to me that here's where we can include the bit about poorly thought-out foreign aid programs, infrastructure problems (power outages), sourcing problems, etc. We should make it clear that it's *tough* to run a business in Senegal and that they're dealing with problems Americans constantly take for granted. We need to see the stakes clearly here.

Mid-Point: Really start raising the tension here. Is there anything Magatte says that has sort of a defeated feel to it? Is there anything we can include here where she's saying that sometimes the problems are overwhelming? This might be the moment for the bit where Miahara says she had no purpose.

Dark Night of the Soul: Fisherman boy lost at sea story goes here. This kid died because he couldn't find work at home. That has to stop.

Act III:

Break into III: Restate the theme again. That fisherman boy wouldn't have been lost at sea, the power wouldn't continually go out, people wouldn't be unemployed and purposeless, people wouldn't be sleeping in a tiny room with their wives and five kids, etc., if only Senegal embraced entrepreneurship. This should be our final and best moment of Magatte making it crystal clear that entrepreneurship is the way out of these problems.

Finale: Magatte is now basically a superhero, bringing jobs and opportunities to people in the poorest parts of the world. We need more Magattes everywhere.

Final Image: Beautiful, sun-bathed Senegal.

As you can see from the film itself, this structure was maintained to the final draft:

Made in Mékhé’s Final Image

It doesn’t matter if the story is true or fictionalized, if it’s one you’re piecing together from interview footage or writing from scratch: Clear dramatic structure is critical.

Without it, a story will not make sense and the audience will be confused (and probably bored). This doesn’t mean that a story can’t be told out of order, or that you can’t shift elements around to toy with the viewer/reader’s expectations, but a story that does not understand where its characters are headed and why is a story that’s destined for disaster.

The Importance of Character-Driven Stories

Now that we’ve discussed the overarching structures and forms of competent storytelling, it’s important to understand that the only thing that makes a specific story worth telling or listening to is its characters.

Plot-driven storytelling is both easy and ubiquitous, but perhaps counter-intuitively, it’s also the quickest way to wind up with a boring narrative filled with logical holes and inconsistencies. A plot-driven narrative is one where characters act because the writer determined that they should in order to advance a predetermined sequence of events, regardless of whether or not it fits with anything that’s been established about the character or his/her motivations.

But… A story is nothing without its characters, and so stories should be driven by believable motivations, and the plot should be subservient to that - just as the sequence of events in our actual lives is determined by our actions, which are determined by our values and desires.

To quote Syd Field, channeing Aristotle:

“Action is character. What a person does is what he is, not what he says.”

Here, I shall also reference David Mamet:

“Every scene should be able to answer three questions: "Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don't get it? Why now?”

…and Robert McKee, whose book “Story” is almost entirely about good character writing. Like Mamet, McKee poses what I think are the most important question any writer is ever going to grapple with:

“Who are these characters? What do they want? Why do they want it? How do they go about getting it? What stops them? What are the consequences? Finding the answers to these grand questions and shaping them into story is our overwhelming creative task.”

Good writing is built on being able to answer these questions and as long as the answers make sense for what we know of the characters in play, the plot will organically reveal itself. If we think this way, it’s easy to bring people into the world’s we’re creating and keep them immersed in the narrative.

On the other hand, if we start with a sequence of events, we will find ourselves forcing characters to do things that cut against their motivations or other traits we know about them simply out of convenience, and that’s a great way to confuse your audience and push them out of the narrative and into an analytical mode - which is the last thing you want if you actually want them to empathize with characters and take anything away from the story after it’s over.

This also brings us back to Brian McDonald’s “story spine”:

Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.”

Note that McDonald does not write, “And then this, ___. And then that, ___. Until finally ___.”

He says “because of that”.

Causality is important to stories, and part of the problem with plot-first writing is that writers end up trying to force characters to do things that don’t make sense and which aren’t informed by their actual motivations, just to get them to work with the sequence of events they’ve already got in mind.

But that’s not how real life works. So it isn’t believable at all.

Plus, remember that in narrative writing (again, quoting Robert McKee):

“A character is no more a human being than the Venus de Milo is a real woman. A character is a work of art, a metaphor for human nature.”

We tell stories to communicate our values and ideas, and if the main characters aren’t believable — if their motivations aren’t clear and if the things that happen to them aren’t caused (or at least influenced) by their choices, the story will have no resonance and cannot actually live up to its purpose.

And to be clear, this is true in every single genre of storytelling — including documentary. The more we can infuse our documentaries with narratives that give the audience a clear picture of who the main characters are, what they want, and to what lengths they’re willing to go to get what they want, the more compelling those documentaries are going to be.

Having produced a ton of documentaries, I can tell you that this is actually really hard in some cases. In fiction, we get to choose the parameters of our world and imbue our characters with the attributes we want — and as a result, our stories can emerge organically in ways that are particularly satisfying for audiences if we do the work of telling them right.

In real life, things are rarely so simple. We don’t always have access to all the pieces we need to understand or share the full context of events with our audiences, and reality has a pesky way of leaving us with a ton of loose ends as people don’t fully resolve their problems. I’ve done several films now where the core antagonists for my subject (the main character in my story) have been unwilling to go on camera. This makes presenting a fleshed-out villain pretty hard. Similarly, I’ve made documentaries where the antagonist wasn’t really a defined individual character at all and was instead just a bureaucracy or a policy that is being enforced by people who had no hand in its creation.

There’s also an awful lot of tragedy for real life heroes, and while that can still be a good story, it’s not what most viewers want to see.

Even so, given the nature of my career, my goal as a filmmaker is almost always to tell stories that have a persuasive quality to them. I want people to watch my films and empathize with the main characters, and in doing so, engage with the ideas they represent.

And that brings us to….

Embedding Persuasive Ideas Into Stories

Earlier I mentioned the concept of “narrative transportation”, which is the idea that:

“To the extent that individuals are absorbed in a story or transported into a narrative world, they may show effects of the story on their real world beliefs.”

That’s a quote from psychology researchers Melanie Green and Timothy Brock, who were among the first to seriously study this phenomenon in their 2012 paper, “The Role of Transportation in the Persuasiveness of Public Narratives”. Green & Brock suggest that an reader/viewer will be transported into the narrative of a given story if the following conditions are met:

People process stories—the acts of receiving and interpreting (ie. they are attentive).

Story receivers become transported through two main components: empathy and mental imagery.

Empathy implies that story receivers try to understand the experience of a story character, that is, to know and feel the world in the same way. Thus, empathy offers an explanation for the state of detachment from the world of origin that is narrative transportation.

In mental imagery, story receivers generate vivid images of the story plot, such that they feel as though they are experiencing the events themselves.

When transported, story receivers lose track of reality in a physiological sense.

The film medium, in particular, has tremendous power to provide these conditions to audiences effectively. Historically, the viewing experience commands undivided attention by taking place inside a darkened theater, thus ensuring that viewers would have the best chance of inherently receiving and processing the story being told. Likewise, through the use of music, editing, and actor’s performances, empathy with a well-written character is virtually guaranteed; while the nature of film as a visual medium can easily aid in the creation of vivid images of the story’s plot. Mirror neuron’s largely do the rest of the work, as people actually feel what they see happening on screen.

Ideally, this means they will be transported into the story world and lose track of reality. You can watch this happening whenever you see people gasp or cry at the movies.

But of course, none of this is really news. The influence that a well-told story can have on the way people think and act has been well-known to writers and storytellers for centuries.

To quote David Mamet again:

“...there are plays - and books and songs and poems and dances - that are perhaps upsetting or intricate or unusual, that you leave unsure, but which you think about perhaps the next day, and perhaps for a week, and perhaps for the rest of your life.

Because they aren't clean, they aren't neat, but there's something in them that comes from the heart, and, so, goes to the heart.What comes from the head is perceived by the audience, the child, the electorate, as manipulative. And we may succumb to the manipulative for a moment because it makes us feel good to side with the powerful. But finally we understand we're being manipulated and we resent it."

The point is, the best and most effective stories are ones that resonate with people emotionally, rather than dealing purely with the intellect.

So, if you're going to use creative media to advance ideas... Simply talking about the ideas themselves and presenting information is never going to be enough. The goal is to get people to feel something, to be moved, and ultimately to be transported into the narrative you’re telling.

To that end, you must find a way to touch their hearts.

What's more, neuroscientists have found that people's ability to be analytical and empathetic operate almost as tradeoffs.

From Popular Science, November 2012:

"A new study published in NeuroImage found that separate neural pathways are used alternately for empathetic and analytic problem solving. The study compares it to a see-saw. When you’re busy empathizing, the neural network for analysis is repressed, and this switches according to the task at hand."

Additionally, per wikipedia:

“In addition to its effects during the encoding phase, emotional arousal appears to increase the likelihood of memory consolidation during the retention (storage) stage of memory (the process of creating a permanent record of the encoded information). A number of studies show that over time, memories for neutral stimuli decrease but memories for arousing stimuli remain the same or improve.[13][26][27]

Others have discovered that memory enhancements for emotional information tend to be greater after longer delays than after relatively short ones.[27][28][29] This delayed effect is consistent with the proposal that emotionally arousing memories are more likely to be converted into a relatively permanent trace, whereas memories for nonarousing events are more vulnerable to disruption.”

[13] LaBar, K. S.; Phelps, E. A. (1998). "Arousal-mediated memory consolidation: Role of the medial temporal lobe in humans". Psychological Science 9 (6): 490–493. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00090.

[26] Baddeley, A. D. (1982). "Implications of neuropsychological evidence for theories of normal memory". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London: Series B 298 (1089): 59–72. doi:10.1098/rstb.1982.0072.

[27] Kleinsmith, L. J.; Kaplan, S. (1963). "Paired-associate learning as a function of arousal and interpolated interval". Journal of Experimental Psychology 65 (2): 190–193. doi:10.1037/h0040288. PMID 14033436.

[28] Eysenck, M. W. (1976). "Arousal, learning, and memory". Psychological Bulletin 83 (3): 389–404. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.83.3.389. PMID 778883.

[29] Heuer, F.; Reisberg, D. (1990). "Vivid memories of emotional events: The accuracy of remembered minutiae". Memory & Cognition 18 (5): 496–50. doi:10.3758/BF03198482.

So, not only do we know that empathetic, emotional engagement leads to far stronger memories and personal influences than does analytical reasoning, it's nearly impossible for people to be rational while feeling strong emotions.

So, how do you embed a theme into a story without it feeling manipulative?

It’s not easy, but the key seems to be to create and tell stories that are an extension of the characters and what those characters would actually do in the world they inhabit. The more believable the story is and the less it forces the audience towards accepting a particular “message” (ie. the less preachy it is), the more effective it will be at inviting people into the conditions that foster narrative transportation.

And once people are sufficiently transported, they will be significantly more receptive to the ideas you’re trying to present (ie. the theme of the story, and even specific lessons contained within).

In the end, this is why effective storytelling is so crucial to people who hope to affect the way people think about the world.

Screenplay Format

Now that we’ve talked about the purpose and meaning of storytelling and the specific approaches to structuring a story that are most effective, we have one last thing to talk about:

Proper formatting.

Practically speaking, writing for the screen and stage is fundamentally different from writing a novel or a short story because the written work will never be read by the intended audience. As a result, the kinds of passages that other writers take for granted - such as detailed descriptions of character’s thought-processes and internal dialogue which can reveal motivations and pertinent plot information - aren’t useful in a screenplay.

As a result, playwrights and screenwriters have developed a specific format for scripts that enables the directors, producers, and performers who will eventually bring the story to life to have access to those kinds of details. This format is fairly simple to adopt, and it makes any type of script-writing substantially easier than it would be if the scripts were treated like novels or other forms of prose.

There are 7 different aspects of any script:

Scene headings

Actions

Characters

Parentheticals

Dialogue

Transitions

Shots

Each of those 7 categories of text gets formatted slightly differently. For example, scene headings are left-justified, all capitalized and sometimes bold.

Actions are left-justified, with standard formatting and punctuation. Important props and main character names will often be capitalized inside action descriptions. This is to help clarify important elements of a scene when it comes time to breakdown the script for shooting.

Character names, in the context of dialogue are center-justified and capitalized. Dialogue is indented and centered underneath the character name. Parentheticals are used to indicate a specific action or mood that the character holds while speaking, and are not always used. When they are used, they’re indented farther right than dialogue and are placed in between the character name and dialogue text.

Transitions (ie. FADE IN, FADE OUT, CUT TO, etc.) are right-justified and all capitalized.

Shot descriptions are left-justified and capitalized, but they are also not generally used by screenwriters. Instead, they’re added later by directors and producers during the process of filming the screenplay.

Here’s an example of the script format taken from the first page of Raiders of the Lost Ark by Lawrence Kasdan:

Learning proper screenplay form is useful for a number of reasons. For one, it helps us to easily see elements of a script and and not get lost in the prose itself. At a glance, I can see the characters and the dialogue, the changing scenes, actions vs. transitions, and more. It also helps us gauge the time our story will take to tell on screen. It’s not perfect, but as a general rule of thumb, screenplay form gives us 1 page per minute.

There are other forms that people who produce video content often use, like the basic A/V format which is arranged in two simple columns — one for dialogue, and the other for associated imagery and sound cues. It’s an easy system, but it’s also ridiculously literal, and I don’t particularly care for it for that reason.

A/V scripts inherently strip a story of all of the important facets of vision and tone that help the filmmaker make better choices throughout the editing process. They mistakenly assume that we can all know in advance what the right visuals will be before we even start cutting a film together, and that completely misses the point of how the creative filmmaking process actually works.

A proper screenplay allows the writer to provide lots of visual details for the filmmaker and editor to work with, but more importantly it allows them to expand on the emotions and tone of the story in a way that bluntly pairing words and images can’t accomplish.

This is important.

The creative process is not linear or obvious. It’s experimental and filled with surprises because its very nature relies on ideas building on other ideas. Quite often, a great idea does not occur to you until very late in the game and a lot of the things that you think are going to work out ultimately don’t.

If the only thing an editor has to go on is a set of images and dialogue cues, they’re not going to understand what they really need to know about the story they’re trying to tell… and they won’t be able to use their skills and experience to make that story better.

Final Thoughts

Writing is a difficult task, and it gets exponentially harder the more ideas you try to cram into a story. If you’re trying to write compelling stories — and especially if you’re trying to write to persuade — my best piece of advice that has not already been said is this:

Keep it simple!

Try to limit your story to one key point, and treat the information you introduce throughout the story with extreme care.

Just as subplots in a fictional narrative should be subservient to and reinforce the main plot (thus improving the clarity of the point of your story), bringing in more arguments and more characters in non-fictional storytelling should be done only when they help support the main idea. If you’re making a documentary, don’t bring in extraneous characters or derail the narrative by going down an unrelated path just because you think it’s interesting.

As a personal example, in my film “Locked Out”, the main story is about Melony Armstrong and her journey to becoming Mississippi’s first fully licensed and legally operating African hair braider. The basic plot is this:

A woman, Melony, has a dream of running her own business braiding hair in Tupelo, MS. But she quickly learns that the Mississippi State Board of Cosmetology won’t allow her to open a salon until she attends an expensive cosmetology school that doesn’t even teach anything about the business she wants to start. She jumps through their hoops only to find that once she’s opened her salon and its proven to be successful, the only way to grow and hire more braiders is to push them to go through the same costly gauntlet she had to endure. For most of her young staff, this is impossible and the ridiculous of the situation causes her to work with a public interest law firm to battle the government and change the law. The fight takes years, but she comes out victorious and now anyone who wants to work as a hair braider in Mississippi can follow their dreams.

It’s a pretty straightforward story, but when I went to Mississippi to shoot the film, I ended up capturing interviews with 25 different subjects and each of those interviews was over an hour of footage.

The final runtime of the documentary is just 26 minutes.

This meant cutting a lot in order to economize the storytelling and bring the main points into focus. The hardest of those cuts was my interview with a woman named Afua Sarah Dave. She was/is a scholar of African American history who lives South of Jackson, MS in an old slave house. I spent hours with her talking about the history of “good hair and bad hair”, and the personal, emotional, and cultural importance of natural hair for black people in America.

I loved that interview.

There’s so much good stuff, and much of it would add helpful context to the overall issue of hair braiding and African American culture. But I cut it.

Why?

Because the film wasn’t actually about “hair braiding”. It was about one woman’s quest to change an unfair law. My conversation with Afua Sarah Dave was awesome, but it was actually a detour from the main point of the film. So as an editor — which, especially in the documentary medium, is effectively a more technical form of writing — I was forced to make a choice that personally made me sad, but which was clearly best for the story itself.

That choice made the film better.

Don’t be afraid to make those kinds of choices, but also make sure they are guided by a clear vision of what story you’re actually trying to tell. That vision is your compass. Follow it.

And good luck writing your story!